YOUR BROWSER IS OUT-OF-DATE.

We have detected that you are using an outdated browser. Our service may not work properly for you. We recommend upgrading or switching to another browser.

Date: 04.12.2019 Category: general news, science/research/innovation, university life, university people

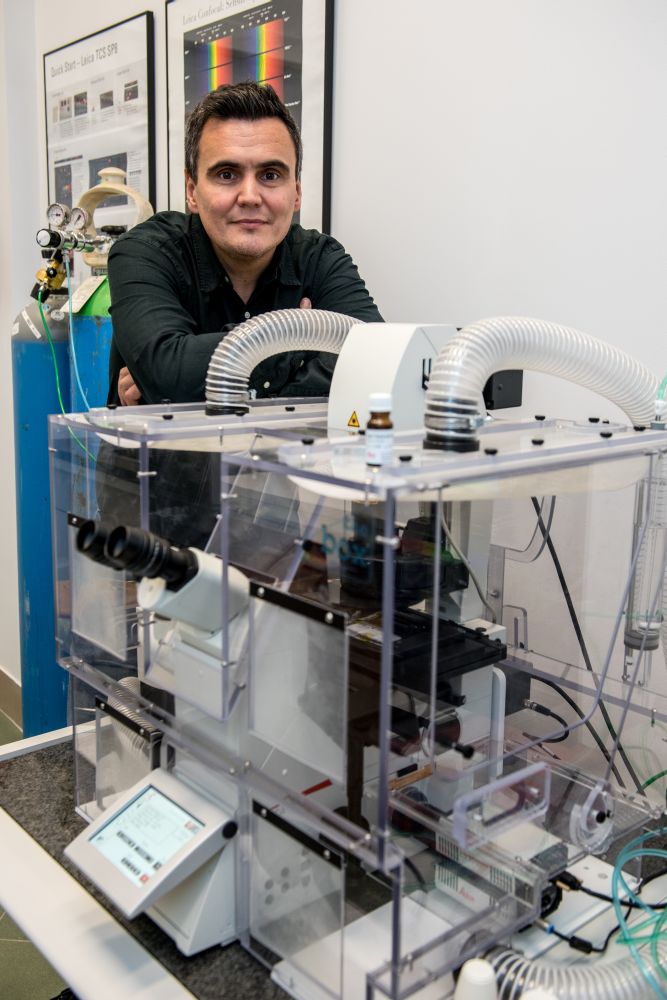

Professor Marcin Drąg from the Faculty of Chemistry has received the award of the Foundation for Polish Science. Thus, becomes one of the winners of the most prestigious scientific award in Poland. - It’s a great inspiration for further activities and pushing the boundaries of knowledge - says Professor Drąg.

The scientific community recognised his research consisting in the development of a new technological platform for the production of biologically active compounds (proteolytic enzyme inhibitors). We have already written more about the Professor’s scientific achievements.

The FNM Award Ceremony took place on December 4 at the Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Interview with Professor Marcin Drąg from WUST’s Division of Bioorganic Chemistry,

who describes his research as "scientific fishing".

Iwona Szajner: You have received a prestigious award for your scientific achievements that "open new cognitive perspectives". Do you realise every day that your research is like this?

Iwona Szajner: You have received a prestigious award for your scientific achievements that "open new cognitive perspectives". Do you realise every day that your research is like this?

Professor Marcin Drąg: I think so since other scientists are interested in it. It’s one of the main indicators for me. If we create something and other people begin to refer to it, continue our research, and use it, it means that we have created something useful.

What does this award, referred to as the "Polish Nobel Prize", mean to you?

There is no denying that it’s the most important scientific award in Poland. First of all, it’s the scientific community’s way to express its recognition of its members. You cannot nominate yourself for this award. For me, it’s a great inspiration for further activity, to constantly develop, push further the boundaries of knowledge, and do better research.

Do you think it’s possible to conduct world-reaching research in Poland?

Of course! I always say that the condition for effective activity in science is the so-called own research subject. I learned this from Americans, who believe that one’s own idea is crucial in this respect. Then others can carry on with the subject. Such projects, ones that are original and interesting, will receive funding both in Poland and abroad.

What if someone is convinced that they are conducting ground-breaking research, then applies for various grants and keeps getting turned down?

This is probably a sign that maybe the research is not as ground-breaking as they think or they simply don’t know how to write grant applications. Excellent projects always defend themselves - if not at one institution, then at another. You should support your own subject with preliminary research. If you put forward something new, it’s not only the idea that counts. As a reviewer sitting on various competition boards, I often see that there are some projects that come out every now and then that we call "science fiction", because they are more about "fiction" than "science". Someone comes up with something, but they don’t test it at all. Whenever I and my team develop a project, we always thoroughly prepare ourselves. We show the results of the preliminary research in the very beginning. By submitting a project application, we show that it’s possible to prove our research hypothesis. Then the chance for funding is very high. In Poland, I’m sure, the evaluation system in such institutions as the Foundation for Polish Science or the National Centre for Science is reliable and just. After all, not only Polish but also foreign reviewers are involved in this process, and the evaluation is a multi-stage procedure.

The idea of research is one thing, but the possibilities of Polish scientific laboratories are a different matter.

The idea of research is one thing, but the possibilities of Polish scientific laboratories are a different matter.

There’s no doubt that universities in the United States, for example, are much better equipped than in Poland. Having said that, this is no excuse whatsoever. After all, we can build specialised laboratories on our own around a given research subject. However, this requires some sort of doggedness. When I came back from the USA over 11 years ago, I started practically from scratch. Someone who is just starting their research won’t immediately receive a huge amount of money to buy absolutely all the necessary instrumentation. You take years collecting it. If your research develops and you successfully carry out projects, it’s possible to retrofit laboratories with more instruments using the new grant money. I’m very sceptical about all those who think that they should get great instrumentation right away and only do their research. Then it often turns out that such people are unable to make good use of their equipment.

Have you always planned to be a professional scientist?

Not really. As a child, I didn't know what I wanted to be in the future. In primary school, I liked biology, and then in secondary school, I was fascinated by chemistry, especially organic chemistry. Then, when I was already studying at the University of Wrocław, I was dealing with classic chemistry, so to speak. And I guess I wasn't exactly enjoying what I was doing. I missed biology. Then the late Professor Józef Ziółkowski told me to do what I like, and what it meant in my case was research into an area where these two disciplines meet. That's why I did my doctorate at Wrocław University of Science of Technology with Professor Paweł Kafarski, who gave me that opportunity, as my supervisor. Then I went on my post-doctoral placement at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla, California, where I learned biochemistry, molecular biology, and a bit of medicine. And that allowed me to build up my knowledge in many fields. Biological chemistry is probably one of the most difficult disciplines to learn because you need to know everything - organic chemistry, biochemistry, enzymology, molecular biology, genetics or the application of biology in medicine. It takes at least eight years to learn it if you want to have a decent understanding, and it’s not about learning one method, as you need to know dozens of them and be able to combine them. What’s more, you also need to smoothly switch from the language of biology to the language of chemistry. I learned it in practice when I was the only chemist to work in a team that comprised only biologists.

Is it science that drives you in your life?

Definitely - science and various discoveries connected with it.

Does the stereotypical image of a scientist who spends their days and nights in a laboratory without understanding everyday life describe you?

I think that this image is strongly exaggerated. If you read the biographies of various scientists, you can see that they usually live normal lives. Take Maria Skłodowska-Curie, for example, who was down-to-earth and knew exactly what she wanted. I know many researchers all over the world, and each of them has some hobbies and exciting interests. They travel a lot and are very open.

I think that it’s openness to the world that makes it possible for us to do research. On the one hand, curiosity and clarity of mind, and on the other, communication skills and interaction with people. After all, you have to be able to talk about your research in such a way as to make others interested. I’ve recently heard a certain professor say that poor scientists only lock themselves in their laboratories because they don’t have enough knowledge to share it publicly and face criticism. I think there must be something to it. Another feature of good scientists is that they are able to talk about their sometimes very complicated research in a simple and accessible way.

Do you know how to do that? For example, by explaining to your children what their dad does?

My children aren’t so small any more, as they are 12 and 14 years old. And they have already managed to "grasp" that my profession is a chemist. I help them a little with their school work and explain things, but generally, they have no big problems with this subject in school. My older daughter is even in a biology-chemistry class.

Is she going to follow in your footsteps?

The biggest mistake, made by many parents, is to prod your children to pursue your own profession. I’ve had many conversations with students, who admitted to fulfilling the ambitions of their parents, making them study chemistry. And I saw that these young people had no heart for it at all, and they even hated the studies. They’d definitely prefer to do something different in their lives. So I’m definitely not going to force my children to do chemistry as researchers.

Unless they want to, seeing how much fun it gives you?

Yes, only on this condition! Interestingly, no one in my family had ever been involved in chemistry before. Moreover, I am the first person with a higher education background in my closest family.

Do you need any predispositions to work in the field of science?

You have to be a manager, be able to manage yourself and others, be open in dealings with others, and not be afraid of criticism.

Was there anything that pushed you towards the world of science?

I always liked Villee's book "Biology". I remember reading it with great pleasure in secondary school. The second such important title for me is the encyclopaedia "Larousse. Earth, plants, and animals". It's probably thanks to this book that I was bitten by the science bug. I found it in a library and read it from cover to cover. Now I have these two books at home on a shelf and treat them like the bible.

What do you read during your long journeys?

I travel a lot, often by plane, but it’s mainly a time to relax and rest. I try to switch off completely. I put on my soundproof headphones and listen to music. And it's very different - from classical music, through jazz, to heavy metal and even sometimes techno. All in all, music is with me all the time. I go to work on foot - about 7.5 km - or cycle. Then I always have headphones on and I’m listening to something.

You spend your free time fishing.

You spend your free time fishing.

Apparently, when I was a toddler, my favourite toys were fish. As an older child, I loved books about fish - they were the best gifts or rewards for me. I also had an aquarium (and I still have one). I got my first fishing rod from my neighbour when I was a few years old. He saw how passionate I was about fishing. Then I started to go fishing with my friends. In the beginning, it was at a pond close to my grandparents’ place near Strzegom. And again, nobody in my family had such interests. So I don't know where it came from. I learned everything myself from books. I used to fish a lot, but I took a short break while writing my doctoral thesis because I simply didn't have time. But when I went to the States, I found myself in a Mecca for anglers. When I saw what kind of fish can be caught there, it all became revived with double strength.

And we’re talking about serious fishing, as opposed to afternoons spent by the river Odra?

That's right, but sometimes a few hours by the nearby river can also be a good way to relax. Having said that, I am fascinated by salmonid fish in the first place. I take part in foreign expeditions that last a week or two. The farthest places where I have fished are Patagonia and Mongolia. I also like Iceland and the north of Russia very much. These are often expeditions during which we’re completely cut off from the world.

And this is what fascinates you the most?

I specialise in fly fishing and angling with spinning gear. It’s a very active way to spend your time. What’s more, you spend time in the bosom of nature, alone with yourself, and there’s certain unpredictability about it. I think that my passion for science and my hobby can be described with the common term "fishing". As far as research goes, you fish out one or two combinations of compounds from a million. It’s the same when it comes to fishing. You don’t know what you’ll catch - what will be attracted by your bait.

Your biggest fishing success?

Your biggest fishing success?

In Patagonia, I managed to catch a Chinook salmon, which is every angler's dream. Iceland has the largest stream trout in the world, and I caught a few of those. As for Mongolia, I went there to catch taimen, which is considered to be a dinosaur fish, as it were, the ancestor of all salmonids. And here, I must point out that most of the specimens we catch are released back into the water as soon as we take a picture. We use methods that mean as little harm done to the animals as possible.

Let's go back to science for a while. What are your plans after the "Polish Nobel Prize"?

In no way do I hunt for prizes. It’s simply the crowning of a certain stage of my professional life. I’m going to keep doing what I’ve been doing so far, because scientific discoveries fascinate me the most. I’m not planning to leave Poland for sure. I have a great team at Wrocław University of Science and Technology and a laboratory with state-of-the-art equipment, to be found nowhere else in the world. There’s no need for me to leave. Here I can do everything I want.

Iwona Szajner

Our site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with current browser settings. You can change at any time.